The Slave Went Free

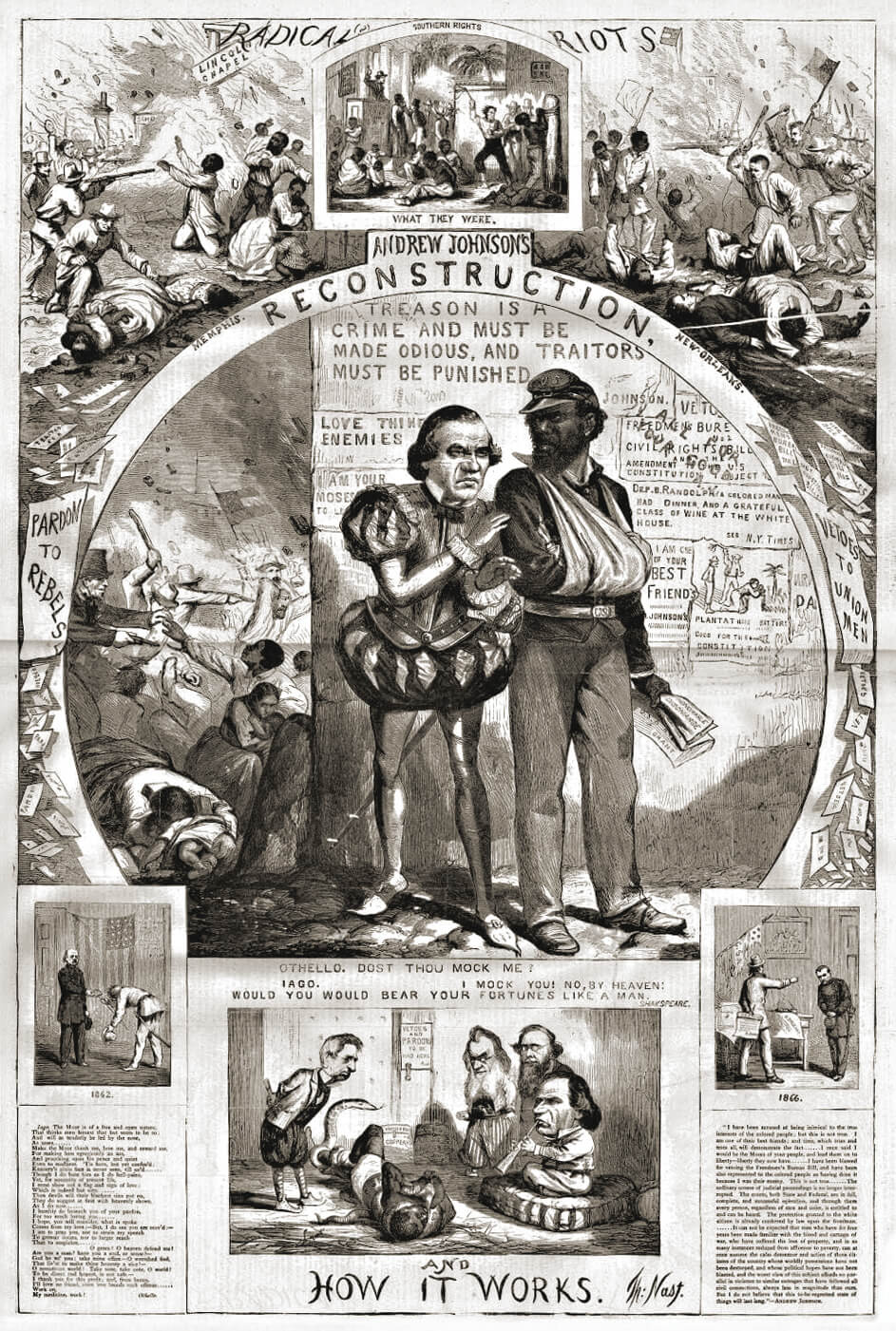

Thomas Nast'due south September 1866 political cartoon shows President Andrew Johnson as Iago, who betrays Othello, depicted as a black veteran of the Civil War. (Library of Congress)

Stony the Route: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.; Penguin Press, 320 pp., $xxx

In Black Reconstruction in America (1935), W. Due east. B. Du Bois wrote, "The slave went costless; stood for a brief moment in the sun; then moved back once again toward slavery." The forces that pushed the freedmen back and how the blackness community responded are the subjects of Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s Stony the Road, its title taken from James Weldon Johnson's 1900 poem "Lift Every Voice and Sing." Gates, a distinguished scholar, filmmaker, and critic, writes with clarity and force nigh Reconstruction, Redemption, and the problem of representation. He describes his book—a combination of text and visual essays—as "an intellectual and cultural history of black agency in the face of white supremacy and resistance to it."

In the spirit of Eric Foner's Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution (1988), Gates views Reconstruction every bit a revolutionary moment in American history. He emphasizes the importance of the Ceremonious Rights Deed of 1866, and ratification of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, likewise every bit efforts past African Americans to build "businesses, churches, schools and other legacy institutions." He reminds u.s. that, during the catamenia, there were at to the lowest degree 2,000 elected black officeholders, including ii United States senators and xx representatives. With citizenship and voting rights assured, Frederick Douglass wrote in 1870, "at terminal, at last the blackness human has a time to come." How, Gates asks, was Reconstruction "allowed to fail"? The answers, he suggests, "are relevant to understanding our contemporary racial politics."

Reconstruction yielded to Redemption as white Southern Democrats "redeemed" their land governments from Republican control, which they derided as "Negro rule," and crafted a multifaceted racist ideology. Critical to this process of dehumanization was "a stock-still prepare of signs and symbols" that denigrated freed people and led to the invention of the "Old Negro," the portrayal of blacks as uncivilized, illiterate, and childlike, but also dangerous. Gates meticulously unravels the strands of this discourse that led one writer to conclude that all "scientific investigation … proves the Negro to be an ape."

White southerners asserted supremacy through the practice of lynching (justified by the myth that black men rape white women), implementing a legal organization of segregation, and producing literature that perpetuated racist stereotypes. Uncle Remus, for example, a black character popularized by Joel Chandler Harris in a book of folktales published in 1880, represents the contented plantation black homo as imagined by whites. The epitome would accept staying power, made central to the motion-picture show Vocal of the Southward, released in 1946, only since 1986 kept out of public view in the United States by Disney.

Gates argues against such self-suppression because racist representations are key to understanding the compages of white supremacy. The Birth of a Nation (1915) did more than any other work to legitimize Redemption and promulgate antiblack racism. Nosotros continue to view it, but differently now than originally intended. Gates includes ii pages of images from the moving picture, evidence of how the culture manufactured a fear of black men and justified white dominion.

The book's visual essays are much more than illustrations of points made in the text. They force readers to meet and feel what African Americans experienced. The repeated dissemination of what Gates calls "Sambo art" created a portrait that not only justified Jim Crow and disfranchisement but likewise became an archetype that "black people would meet when they saw themselves reflected in America's social mirrors."

Gates decided to include these powerful images "without comment," writing that "they speak for themselves." But I wish he had presented them with the same sophistication he brings to his assay of literary works. Images do not speak for themselves; like a text, they must be read. This is especially true for political cartoons, such as Thomas Nast's "Reconstruction and How It Works" (1866), which is filled with references to specific acts of violence against blacks and portrays Andrew Johnson as Iago, who betrays Othello, depicted as a blackness Ceremonious War veteran. Non every image requires extended explication, but many deserve further historical and visual analysis.

Gates combines the literary and the pictorial in his final chapter on the New Negro. Best known as an expression of the Harlem Renaissance, and given prominence with the publication of Alain Locke's 1925 album of that proper name, the construct dated to the belatedly 19th century and marked what Gates calls "a war of representation" every bit blacks sought to "have back their paradigm from the choking grasp of white supremacy."

Disquisitional to this motility was photography. In 1900, at the Paris Exposition, Du Bois curated the Exhibit of American Negroes, which contained more 350 photographs of center-class, respectable, and cultured black men and women. Just every bit everyone in the photographs looked different, so too was at that place never ane version of the New Negro. Du Bois's "talented tenth," which raised course differences inside the black community, contested with the conservatism of Booker T. Washington, the nationalism of Marcus Garvey, the activism of William Monroe Trotter, and the socialism of A. Philip Randolph.

Gates is aware that progress can atomic number 82 to self-approbation, perhaps never more so than when some proclaimed the ballot of Barack Obama as the offset of "a postracial America." The lessons of the past require continued activism, he argues, and he admonishes those who think cultural expression is a form of power: "No people, in all of man history, have always been liberated by the cosmos of art. None." But Gates also knows that art can inspire. He calls jazz "the world's greatest art class" and quotes Langston Hughes: "jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America: the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world." It may not be a political revolution, but it sounds similar liberation to me.

Source: https://theamericanscholar.org/how-the-south-rose-again/

0 Response to "The Slave Went Free"

Post a Comment